COVID-19 and its Significance for the Horse

Overview of COVID-19 and its Significance for the Horse

Commentary by Peter Timoney, MVB, PhD, FRCVS, Professor, Frederick Van Lennep Chair in Equine Veterinary Science at the Gluck Equine Research Center

Events worldwide over the past several months are a grim reminder of the potential ability of a novel infectious agent to cause widespread illness in naive human populations that can result in the death of an alarmingly high percentage of seriously affected individuals.Since initial discovery of SARS-CoV-2, the causal viral agent of the disease COVID-19, in December 2019, that exact scenario has played out in an ever-increasing number of countries around the world. The unique ability of this newly discovered virus to spread through direct or indirect respiratory contact between people within a matter of a few months, resulted in a global pandemic that the human race has never before been exposed to nor had to deal with. The impact that this on-going pandemic is having on the health and economic well-being of human societies worldwide is beyond comprehension at this time.

Events worldwide over the past several months are a grim reminder of the potential ability of a novel infectious agent to cause widespread illness in naive human populations that can result in the death of an alarmingly high percentage of seriously affected individuals.Since initial discovery of SARS-CoV-2, the causal viral agent of the disease COVID-19, in December 2019, that exact scenario has played out in an ever-increasing number of countries around the world. The unique ability of this newly discovered virus to spread through direct or indirect respiratory contact between people within a matter of a few months, resulted in a global pandemic that the human race has never before been exposed to nor had to deal with. The impact that this on-going pandemic is having on the health and economic well-being of human societies worldwide is beyond comprehension at this time.

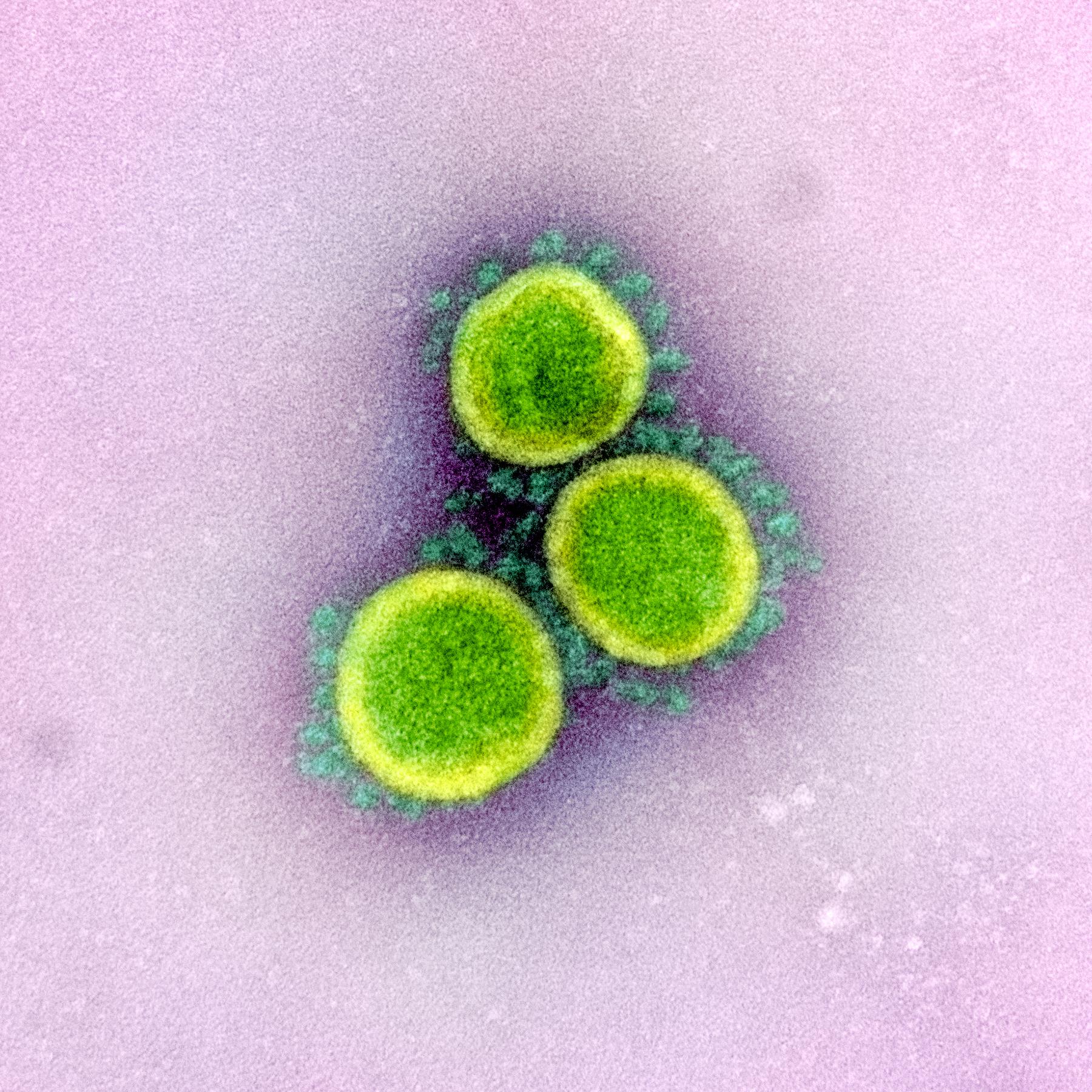

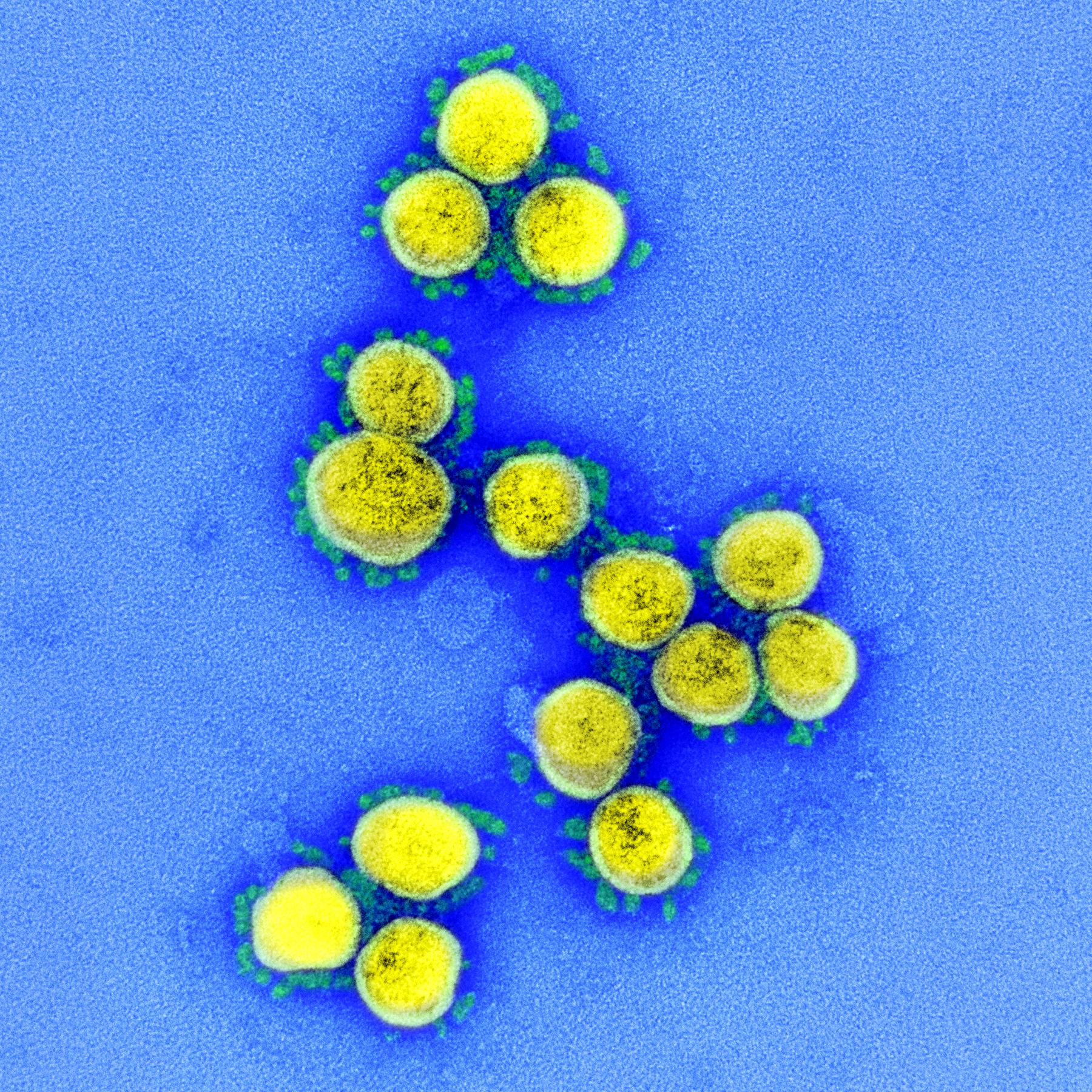

The disease in question that has been termed COVID-19, is caused by a previously unknown virus (SARS-CoV-2) that is a member of the coronavirus family. Viruses of this family are so named because of their crown-like structure and morphology when visualised by electron microscopy. This is not the first coronavirus to have emerged within the last 15 to 20 years that has turned out to be a major human pathogen. There have been three in all, each capable of causing serious and frequently life-threatening respiratory disease in humans. The first was SARs-CoV, the cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) first reported in PR China in 2002. The second was MERS-CoV, the cause of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) that was first identified in Saudi Arabia in 2012. All three coronaviruses are highly important human pathogens, each contagious and capable of causing widespread disease and a variable mortality rate.

Coronaviruses are a group of diverse viruses that have been found in a wide range of host species, both mammals and birds, besides humans. Members of the family can cause respiratory or intestinal disease in certain domestic species such as horses (equine coronavirus infection), swine (transmissible gastroenteritis), cattle (winter dysentery), cats (feline infectious peritonitis), and chickens (infectious bronchitis) to name some of the more important diseases.

Coronavirus infection in horses, first identified in the early 1970s, can be associated with a range of clinical signs in the horse. These can range from fever, depression, diarrhea and colic to fever, diminished appetite, depression without any enteric (in the intestines) or intestinal involvement to asymptomatic infections. Based on field outbreaks of the disease, only about 20% of infected horses develop signs of clinical illness with soft feces and the occasional case of colic. Fewer than 5% of cases may exhibit signs of neurologic involvement that is believed to be attributable to hyperammonia (and excess of ammonia) in the enteric, or intestinal, tract.

It is evident from the foregoing that coronavirus infection in the horse is an enteric and not a respiratory disease. This is similar to coronavirus-related diseases in swine and cattle. The coronavirus that affects chickens, although primarily a respiratory pathogen, can also infect the urogenital (involving the urinary and genital organs) and gastroenteric systems. Feline infectious peritonitis (inflammation of the serous membrane lining the cavity of the abdomen and covering the abdominal organs) in cats is an immune-mediated disease. The primary clinical syndrome caused by members of the Coronavirus family will vary depending on the virus in question and the host species it infects.

It is important to emphasise that SARS-CoV-2 is a totally distinct coronavirus from equine coronavirus or the coronaviruses that cause disease in the other domestic animal species. Furthermore, there has never been any indication since its original discovery that equine coronavirus has caused infection in humans.

It is not surprising in light of its recent emergence, that there are many aspects of the biology of SARS-CoV-2, its epidemiology and the pathogenesis, or disease development, of COVID-19 that remain to be clarified, although this is rapidly changing. The outcome of comparative genomic analysis would indicate that this virus very likely originated in bats. It is known that bats are a major natural reservoir of highly diverse SARS-like CoVs. Previous studies established that bats were the original source of both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.

It should be noted that in the case of both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, interspecies transmission to humans did not take place directly from bats. An intermediate host was involved, which in the case of SARS-CoV was the Himalayan palm civet or the racoon dog, and in the case of MERS-CoV, the dromedary camel. Although not yet established in the case of SARS-CoV-2, it is probable that an intermediate host or hosts was also implicated in the interspecies transmission or “species jump” of this virus to humans. Among the species under investigation as possible intermediate hosts are the pangolin, Chinese krait and cobra snakes. Circumstantial evidence would indicate that “wet markets” in cities and towns in PR China where a wide variety of wildlife are traded, are the sites where it is believed humans can be exposed to a particular species of animal that is infected with SARS-CoV-2. A second “species jump” of the virus would be needed for humans to be successfully infected and for human-to-human transmission to take place.

With reference to virus transmission, it should be pointed out that the principal means of dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 is very different to that of equine coronavirus. SARS-CoV-2 is spread primarily by the respiratory route through the dispersal of aerosolized infective secretions from acutely infected individuals; by contrast, equine coronavirus is transferred between horses by consumption of fecal contaminated material (oral-fecal route).

A point of major and continuing concern is whether given appropriate circumstances, SARS-CoV-2 is capable of infecting horses and other domestic and wildlife animal species. At this point in time, there are no reports of the virus infecting or causing disease in horses nor is there any reason to believe that horses have a role to play in the transmission and spread of the virus.

Isolated cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection have however been confirmed in other domestic species, specifically dogs and cats. Two dogs in Hong Kong and one cat in Belgium were diagnosed with the virus; in each instance, their respective owners were positive for COVID-19. While no clinical signs were reported in either dog, the cat developed vomiting, diarrhea and respiratory issues associated with the infection. In a recent report from the PR China, samples collected from clinically ill dogs (4) and cats (20) in Beijing, were all negative for SARS-CoV-2 genetic material. On the other hand, a study of 102 cats in the city of Wuhan, epicenter of COVID-19, provided serological proof of exposure to the virus in 15% of the cats but no evidence of active infection with the virus.

Apart from confirmed reports of SARS-CoV-2 in dogs and cats, infection with the virus has also been recently reported in wildlife. A Malayan tiger that developed a dry cough and reduced appetite was confirmed positive in the Bronx Zoo in New York. Several cohorts to this case displaying similar clinical signs, although not tested, may also have been cases of infection. Additional information on the host range of SARS-CoV-2 is provided in a report of a study of tissues from 775 farmed mink, foxes and racoon dogs harvested in PR China between 2016 and 2019. All of the samples were negative for genetic material of the virus.

Aside from the reports of natural SARS-CoV-2 infection in dogs and cats and a tiger, an experimental in-depth study has been undertaken of the susceptibility of a range of animal species that can come into close contact with humans in the PR China. Of the species investigated, pigs, chickens and ducks were found not susceptible to infection; dogs were poorly susceptible; and cats and ferrets were highly susceptible following exposure to the virus. Respiratory transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was demonstrated between challenged and in-contact cats.

Several recent publications have shown that SARS-CoV-2 uses angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as its receptor to enter human cells. This protein is expressed on the surface of certain cells in the respiratory tract. Feline ACE2 receptor bears close similarity to the human ACE2 homologue based on its amino acid composition; this may well explain the apparent susceptibility of cats and probably other members of the family Felidae to SARS-CoV-2.

While currently there is no information on the potential susceptibility of the horse to infection with SARS-CoV-2, one published study has shown that the ACE2 host-cell receptor in the horse has similarity to its human ACE2 counterpart. The significance of this in terms of determining susceptibility of the horse to the virus remains to be seen. It should be re-emphasised that at this point in time, there is no reported evidence that SARS-CoV-2 causes infection or disease in the horse nor that horses play any role in the transmission and spread of the virus.

Undoubtedly, the state of knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 will continue to be updated in the coming weeks and months. The availability of new information on the virus and the disease should help better define and improve our understanding of the susceptibility of the horse and other domestic and wildlife animal species to the virus and delineate what role if any certain species might play in the epidemiology of this highly important human pathogen.