An Equine New Year’s Resolution: Better Pasture Management

The beginning of a new year is a great time to set priorities for the rest of the year. Focusing some of our efforts on improved pasture management could potentially have positive impacts on our horses, our wallets and the environment. Like many resolutions, it is a yearlong undertaking that requires advanced planning.

Benefits of Improved Pastures

Improving pastures has many benefits that justify the time, effort and potential cost involved. Pastures that have desirable grass cover provide safe footing for horses and, in many cases, all of the nutrition needed to maintain them.

“The most economical way to feed a horse is on pasture,” said Tom Keene, forage agronomist at the University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, Food and Environment.

Stored feeds, such as grain mixes and hay, are significantly more expensive than maintaining a healthy and productive pasture. Weed control in pastures improves the quality and quantity of forage produced, is more aesthetically appealing and reduces toxic plant growth. Finally, a healthy pasture reduces manure and fertilizer runoff into nearby waterways and slows soil erosion.

Planning Ahead

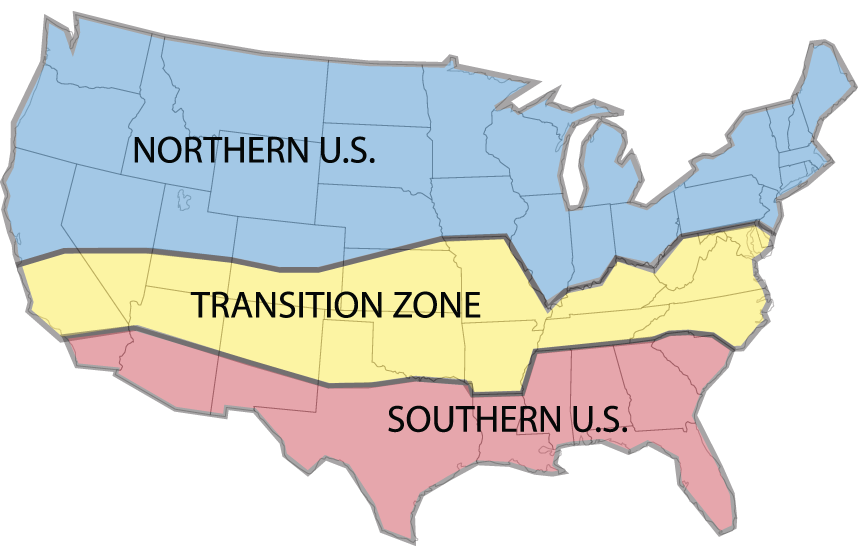

Improving pastures in an economical way requires knowing “the what,” “the how,” and “the when” concerning pasture management. Knowing when to carry out specific practices can sometimes be difficult due to climate differences across the United States. Northern states tend to be dominated by cool-season grasses (those that grow best when temperatures are between 60°-80°F). Southern states favor warm-season grasses (those that grow best when temperatures are 85°-95°F). Transition Zone states, like Kentucky, are in an area where farms can utilize both warm- and cool-season grasses (Figure 1).

Winter

The goal of winter pasture management is to minimize traffic impact on the pasture. This usually means removing horses from pastures or limiting their access, especially during wet periods. Keep horses in a “sacrifice area” during winter months, as heavy traffic will damage most grasses that are now dormant. Exceptions include grazing stockpiled tall fescue, bermudagrass or annual ryegrass.

Stockpiling refers to setting aside grazing areas in the late summer or early fall and allowing forage to accumulate for grazing in the early winter, therefore reducing the need for feeding as much hay. Think of stockpiled forage as hay still standing in the pasture rather than stacked in the barn. Harvesting, baling, transporting and storing hay is an expensive process; grazing stockpiled grasses allows the horse to harvest the forage in the field, saving you money and time. Grasses such as bermudagrass and tall fescue are excellent for stockpiling because they hold their nutritive value after a killing frost and will survive winter grazing well (when managed properly). Pastures dominated by grasses such as orchardgrass and bahiagrass are not good candidates for stockpiling, as freezing temperatures lower their quality, and winter grazing easily damages them.

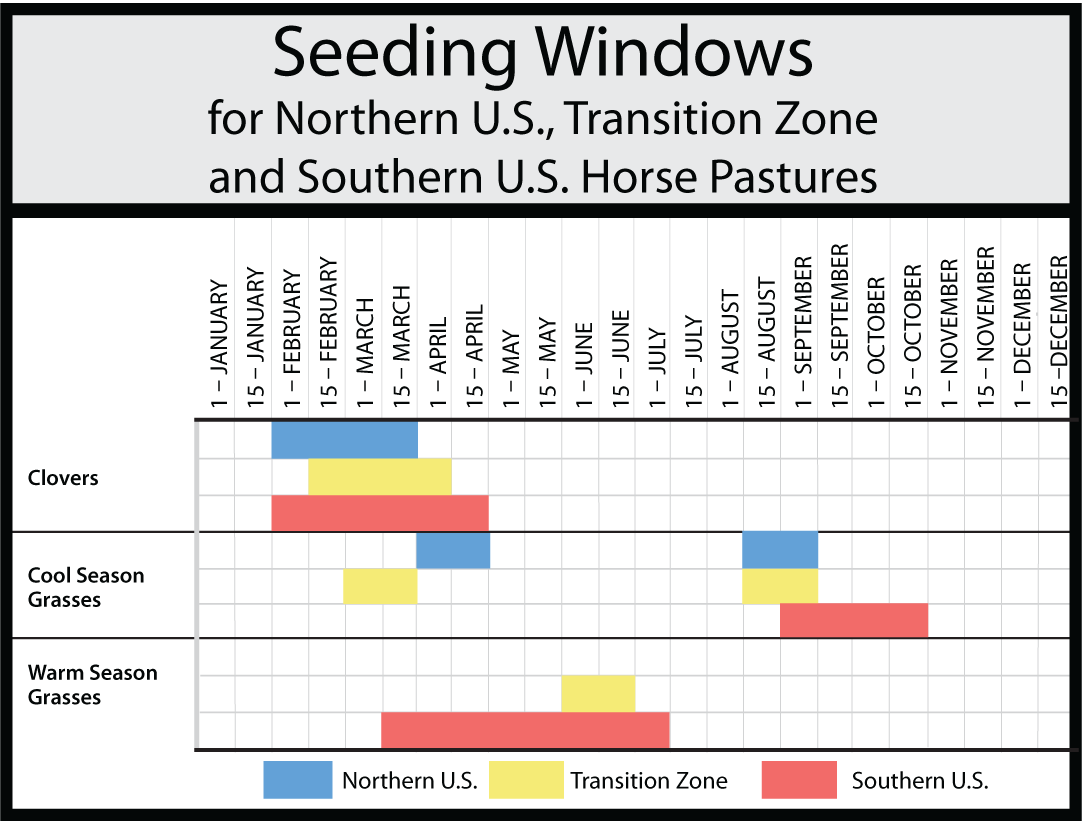

Frost seeding clovers into pastures improves forage quality and production. Perform frost seeding in late winter. Broadcast clover seeds four to six weeks before the last frost into pastures that have been either grazed heavily or mowed close. As the ground freezes and thaws, it will expand and contract, working seeds into the soil. These seeds will germinate in early spring. Do not frost-seed grasses and other legumes such as alfalfa, as their success rates are low. Whenever seeding, always use quality seed of improved varieties ideal for your area.

Spring

Spring is all about balancing quality with quantity. Pastures dominated by cool-season grasses will be extremely productive and begin producing seedheads during the spring. Forage quality and maturity are inversely related, meaning that as the plants mature, yield increases while forage quality decreases. Many farms produce more forage in the spring than their horses can keep up with. In these situations, mow or divert excess forage into hay production. Mowing will also remove seedheads, keeping grasses in a vegetative state and improving the pasture’s forage quality.

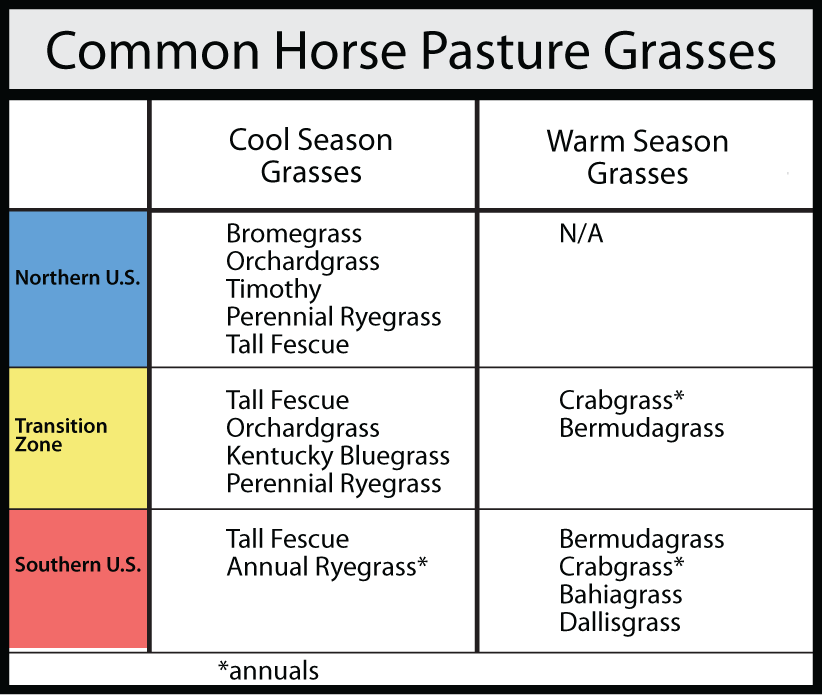

Seeding is another springtime task. For southern areas, spring and early summer are the only times to seed warm-season grasses such as bermudagrass. Seed or plant bermudagrass via vegetative propagation (planting sprigs). Any planting’s success rests on proper preparation, including weed control and fertility. You can also seed cool-season grasses in the spring, but ideally seed them in the fall, especially in the transition zone and the southern United States. Figure 2 contains a list of common cool-season and warm-season grasses for different areas.

Naturally occurring tall fescue (usually KY 31+) is known to be infected with an endophyte that can produce chemicals toxic to broodmares. This is a significant concern in the transition zone where tall fescue is dominant and large broodmare herds are common. If significant tall fescue is present in pastures, remove broodmares from it during their last trimester. Have the fescue analyzed for endophyte and ergovaline (the toxic chemical) presence in the late spring/early summer, when ergovaline levels peak.

Summer

Summer is all about managing warm-season grasses. This is the time of highest production for warm-season grasses. Horse farms in the south will typically be grazing pastures heavily during this season and haying excess forage. Bermudagrass is very responsive to nitrogen applications; if maximizing yield is important (such as when making hay) add nitrogen applications in the summer. However, if there are not enough horses to consume the forage produced, reduce your nitrogen applications.

In northern locations, most warm-season grasses are considered weeds. Crabgrass is one warm-season grass that is very nutritious for horses (and they like it). However, it and other warm-season grasses are not desired in cool-season pastures because they die back in the fall, leaving bare areas that problem weeds can fill in. For cool-season pastures, summer is a time to reduce grazing pressure to prevent warm-season grasses from invading. Additional supplementation might be needed in the transition zone, where summer temperatures can persist for extended periods of time and cool-season grass production is low.

Summer is also the time to start planning and preparing for late summer or early fall pasture establishment. Some farms choose to kill pastures completely and re-establish new pastures to greatly improve forage quality and quantity. This usually requires one to two applications of glyphosate to remove all vegetation. High rates of glyphosate are best when controlling difficult grasses such as tall fescue and nimblewill (a warm-season perennial grass that livestock do not consume). Space glyphosate applications about six weeks apart; apply the first application in the late summer to set up for a proper seeding window in the fall. After the second application, you can reseed grasses one week later due to glyphosate’s low residual effects. When using herbicides, always read and follow all label recommendations.

Fall

Fall is all about planning for the future. This is the best time to seed cool-season grasses, re-establish pastures that were killed over the summer and overseed by drilling into existing stands. Overseeding perennials into thin cool-season stands will thicken the stand while overseeding annuals (such as oats, cereal rye or annual ryegrass) into warm-season grass will provide fall and spring grazing. See Figure 3 for recommended seeding dates. Grasses are best established using a no-till drill. Seeding rates will vary by species and mixture; seeding too little can result in thin stands and high weed pressure while seeding too much is a waste of seed (and money).

Nitrogen is the most important nutrient for grass production. Late summer through fall is the best time to fertilize cool-season pastures with nitrogen. This will allow grasses to be productive longer into the winter without the excess production that is common with spring applications. You can split nitrogen applications into two applications (primarily in the transition zone) six weeks apart. Nitrogen applications in late summer are especially important when stockpiling forages for winter.

Do not graze tall fescue or bermudagrass pastures that are being stockpiled in the early fall. These pastures will accumulate forage (aided by nitrogen applications) and can be used when needed in the winter.

Year-Round Practices

Rotational grazing can benefit pastures throughout the grazing season. Horses are spot grazers, meaning that they will repeatedly graze the same location over and over again while ignoring other areas. By rotating horses and clipping pastures after horses are removed, you can reduce spot grazing’s impacts. Rotational grazing is simple: Moves horses from one pasture to another and back again every few weeks. Use temporary fencing to divide pastures, if needed.

You can sample soil and apply fertilizer (excluding nitrogen) anytime the weather is conducive. Ideally, sample pasture soil every two to three years, and apply lime and fertilizer based on soil test recommendations. Local county extension agents and agribusinesses are great resources for soil testing recommendations.

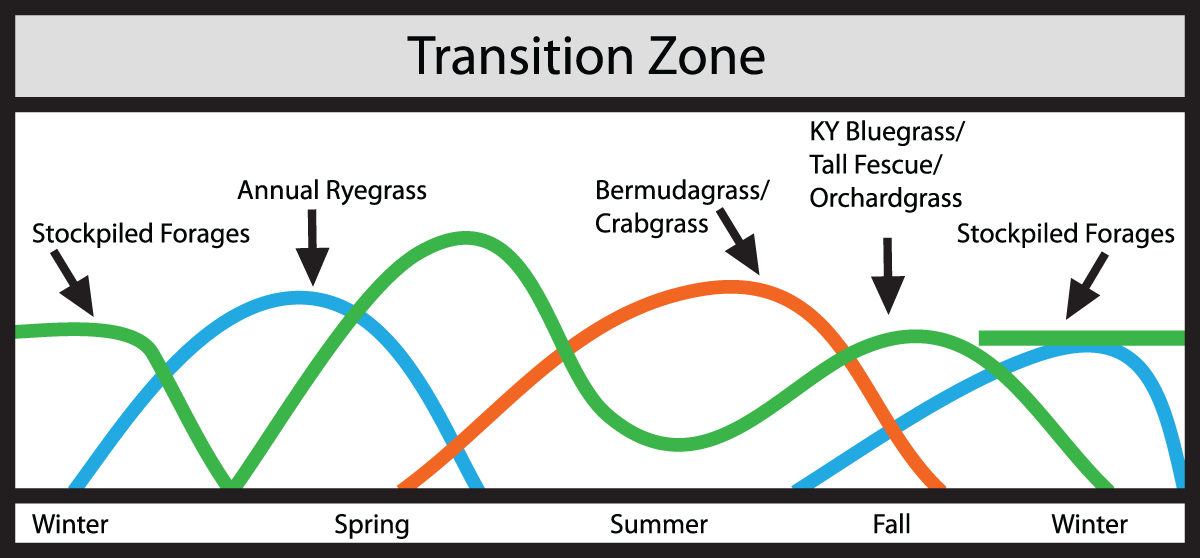

A good pasture management strategy will focus on providing and utilizing quality grazing throughout most of the year. Figure 4 illustrates yield distribution for grasses that farm owners can plant in the transition zone. Pastures dominated by cool-season grasses (such as tall fescue and orchardgrass) will be most productive in the spring and the fall. During summer, horses will be grazing warm-season grasses, like crabgrass. Late fall and into winter, feed them stockpiled tall fescue. Seed annual ryegrass in early spring until cool-season perennials become active again. Provide hay if needed in the late winter or peak summer months when forage production does not meet your horses’ nutrient requirements.

Weed Control

Unfortunately, weed control is not a once-a-year event. It’s highly dependent on the weeds present. Generally, weeds are best controlled in a young, vegetative state; however, they often go unnoticed until they are big and strong. Like grasses, different weeds dominate pastures during certain times of the year. Spring weeds include buttercup, chickweed, purple deadnettle, henbit and yarrow. Summer weeds include pigweed, wild carrot, cocklebur, tall ironweed and ragweed. Fall weeds include plantain and dandelion.

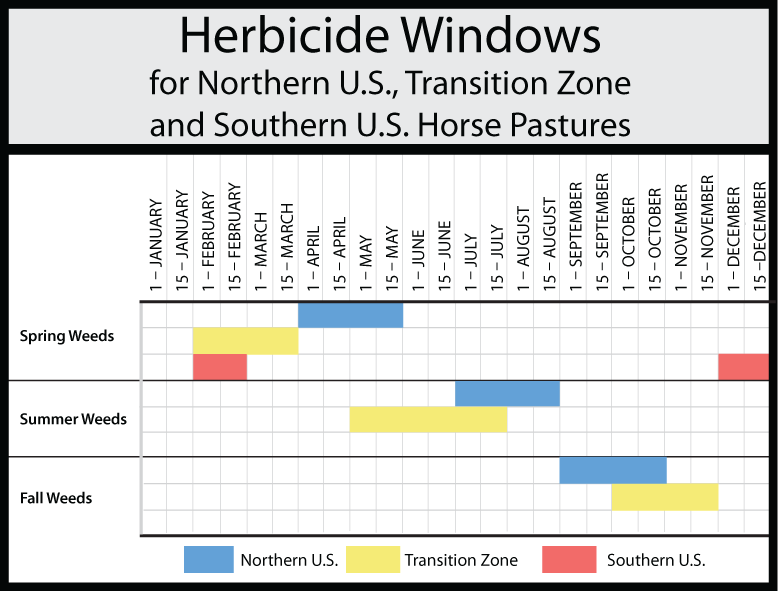

The key to successful herbicide control of weeds is applying the correct herbicides for the target weed at the correct time. This means some pastures could require more than one application per year until weed populations decrease. Herbicides that are safe for established grasses are often not safe for new seedlings; you might need to focus on weeds one year and worry about grass establishment the next (or vice versa). Figure 5 contains recommended treatment windows for groups of weeds throughout the various climate zones. Always follow label instructions when using any herbicide.

Many pasture management practices will also impact weed control. Mowing weeds before they produce seeds can reduce future populations. Maintaining proper fertility will give grasses the best chance to outcompete weeds. Overgrazing pastures will open up bare areas in the pasture, giving weeds the chance to establish and spread.

Determining Your Needs

Not every pasture needs all the management practices discussed here every day. Walk through pastures periodically to help determine how and what to focus your attention on. Contact your local county extension agent or agribusiness representative for assistance and planning of pasture management.

Find more information by visiting the following Forage Extension websites:

- Northeast: http://extension.psu.edu/plants/crops/forages

- Transition Zone: uky.edu/Ag/Forage/ForagePublications.htm

- South: AlabamaForages.com

Krista Lea, MS, coordinator of UK’s Horse Pasture Evaluation Program, and Ray Smith, PhD, professor and forage extension specialist within UK’s Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, provided this information.