Justifying Kentucky 31 Tall Fescue No More

While central Kentucky is known as the Bluegrass Region, there is no denying that Kentucky 31 tall fescue is a big part of our pastures. Its presence, rightly so, affects how we manage those pastures. Alternatives to Kentucky 31 have been on the market for decades, but many of us have continued to resist switching to another grass. It’s time for that to change.

Types of Tall Fescue

Before we look at why horse farm managers and owners should be moving away from Kentucky 31, we need to clear up some confusion about the different types of tall fescue. For this discussion, we will lump all tall fescue into three types: Kentucky 31, endophyte-free and novel endophyte.

Kentucky 31 is a specific variety that originated in Menifee County, Kentucky. It was released in 1943 and is now grown on 35 million acres in the U.S. Kentucky 31 has a colorful past, and its proliferation is largely due to the efforts of one entrepreneurial farmer and an eager plant breeder (read the full, fascinating history of KY31 in The Wonder Grass). The original Kentucky 31 variety was highly infected with the toxic endophyte that causes so much difficulty in pregnant mares. It is a safe assumption that most naturally occurring tall fescue in pastures today is Kentucky 31, or very close to it. This tall fescue may also be called wild-type or toxic-type tall fescue. The combination of the plant and the specific endophyte is what makes it durable, long-lasting and toxic.

There are many varieties of endophyte-free tall fescues on the market today. Some have been bred to have softer leaves or greater palatability, but all of them have one thing in common: no endophyte. From a horse perspective, this is a good thing. But remember that the endophyte is what gives the plant the added durability and tolerance to disease, insects, drought, heat and heavy grazing by horses. Without the endophyte, tall fescue is unlikely to survive much longer than orchardgrass, which is about five years or less. For years, these were the best alternatives to Kentucky 31, but still left so much to be desired.

Novel endophytes first showed up in the commercial market in 2000 and have continued to evolve and improve. These varieties result from taking an endophyte-free plant and inserting a naturally occurring, non-toxic endophyte into the seed at germination. The inserted endophyte is not genetically modified but has been collected from tall fescue plants from North Africa and Europe. Once these insertions are made, plants with the new endophyte are evaluated for durability as well as livestock safety. Those that perform well become commercial varieties of novel, or sometimes called friendly or beneficial, tall fescue. All of these have longevity similar to Kentucky 31, but the safety of endophyte-free makes them the best choice for horse pastures as well as for pastures for other livestock species (one novel variety, BarOptima+E34 has been known to produce some low levels of ergovaline, and therefore would not be considered safe for pregnant mares, though is acceptable for other livestock).

Today’s Tall Fescues

Despite the fact that novel endophyte tall fescues now provide us with the best of both worlds and are a very viable alternative to Kentucky 31, horse farm managers and horse owners are still tempted to purchase Kentucky 31.Years ago, there were some justifiable reasons, but those days are fast coming to an end for one simple reason: the Kentucky 31 of the 1940s isn’t the Kentucky 31 of today.

Part of the success and proliferation of Kentucky 31 was the commercial production and fast replanting of newly harvested seed. In the 1940s, when the University of Kentucky was actively commercializing Kentucky 31, it was believed to be a magic bullet, capable of solving many of our grazing problems. Farmers could readily see its superior agronomic characteristics and quickly planted Kentucky 31 as soon as seed was available. Seed quality was closely monitored, and due to demand, seed was planted the same year as it was harvested. The endophyte will survive about a year in the seed bag, so these new seedings were also toxic (and therefore durable) since they arose from infected seed. The quick acceptance and superior durability and yield helped this variety to become as prevalent as it is today.

Now, demand is lower and the bag of Kentucky 31 you purchase this year may have been harvested last year. The degree of endophyte loss is dependent on how the bag was stored and shipped, and how long since it was harvested. These are all details that the end user doesn’t know. And there is no regulatory body that is testing for the presence of the endophyte. You could be getting a very highly infected bag of seed, no infection at all or something in between. Even UK has purchased several lots of Kentucky 31 tall fescue, only to find such a low infection rate that it could not be used in research as planned.

As highlighted earlier, endophyte free fescues persist about the same as orchardgrass. So if you want to avoid tall fescue endophytes completely, it is best to go with orchardgrass, and plan to mow high and replant every three to four years. Even if you do plan to transition an old tall fescue field to a novel endophyte type, rotating through a few years of orchardgrass can help assure you that all of the original toxic tall fescue has been killed.

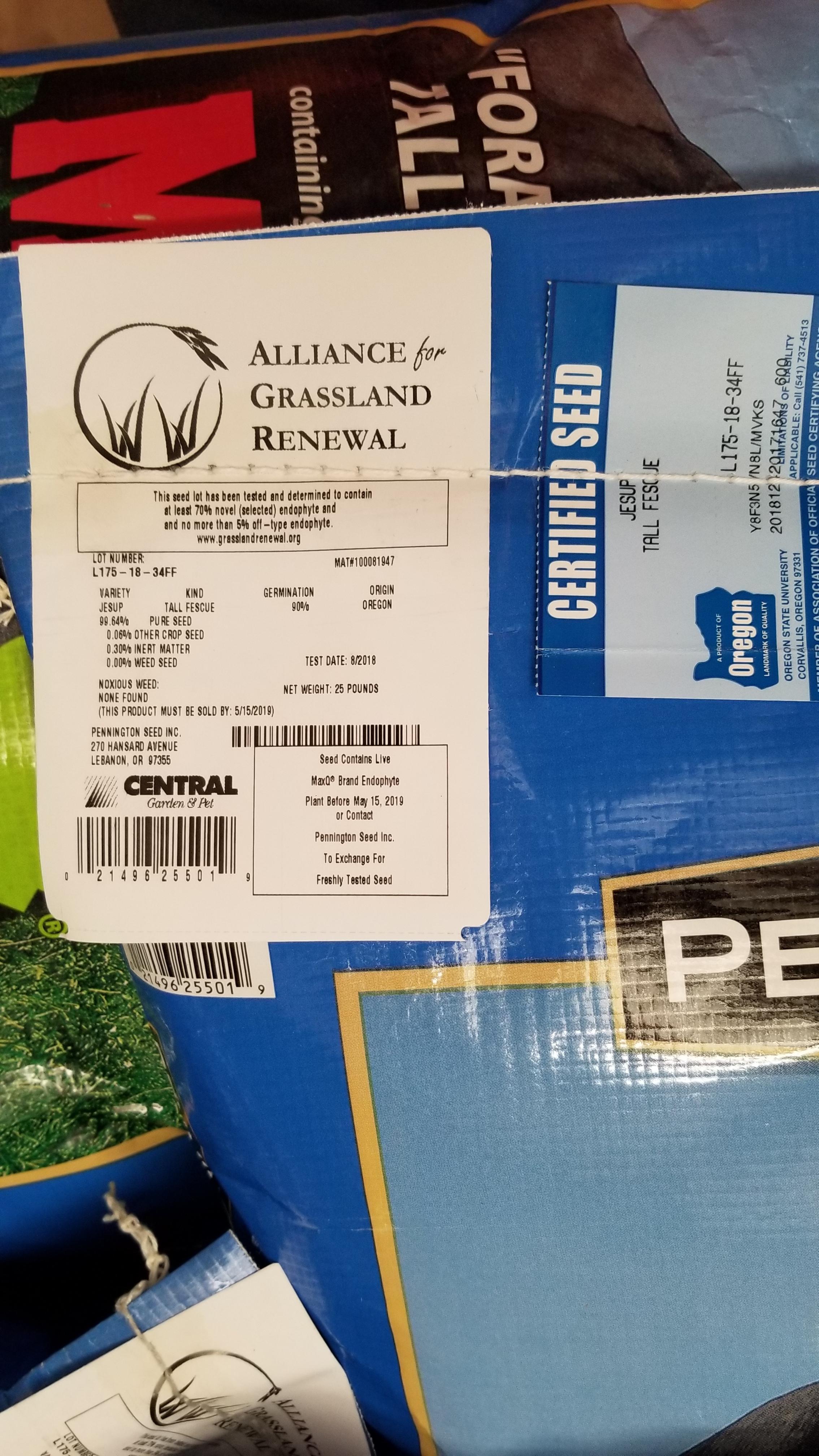

Novel tall fescue varieties have a lot of things going for them. They have been rigorously tested for safety, including for pasturing pregnant mares in studies conducted at UK. Novel tall fescues are carefully tested for germination, purity and especially endophyte viability. This information will be printed on the seed tag of each bag of seed. Additionally, many seed companies have joined to form the Alliance for Grassland Renewal, a nonprofit group which voluntarily imposes an additional level of testing and scrutiny. Varieties from these companies will have an Alliance for Grassland Renewal logo on the bag.

Price has been another major argument against novel tall fescue varieties, but that gap is closing. One farm recently priced out a pasture mixture with Kentucky 31 with a novel variety and found the price for the novel was only $0.45 a pound higher. The safety of novel varieties makes them attractive to broodmare managers, but the durability and longevity should make them attractive to all horse owners. While non-breeding farms may not need to remove their old Kentucky 31 stands, they should certainly not plant the variety anymore.

Price has been another major argument against novel tall fescue varieties, but that gap is closing. One farm recently priced out a pasture mixture with Kentucky 31 with a novel variety and found the price for the novel was only $0.45 a pound higher. The safety of novel varieties makes them attractive to broodmare managers, but the durability and longevity should make them attractive to all horse owners. While non-breeding farms may not need to remove their old Kentucky 31 stands, they should certainly not plant the variety anymore.

Before you do plant any pasture grass, be sure to consider the full process and timing. Fall is the best time to seed cool season grasses, but spring seeding can be successful if done early and the summer is mild. Completely killing out an existing field and reseeding will take a year or more before the field is ready to be used for pasture. Be sure to select improved varieties. Kentucky has an extensive forage variety testing program you can access here: https://forages.ca.uky.edu/variety_trials). It is always a good idea to save back a few handfuls of seed in case there is ever a seed quality question. Double bagged in the freezer, seed will keep for years. Seeding pastures is often the most expensive and risk prone pasture improvement step we can make. Therefore, take every precaution to ensure success. Regardless of what type of horses you own or manage, Kentucky 31 tall fescue is not the best grass available and shouldn’t be included in your seed mixtures.

The Alliance for Grassland Renewal is hosting three novel tall fescue renovation workshops this spring. These workshops focus on understanding the science behind toxic tall fescue, and the steps to successfully convert to and maintain novel tall fescue varieties. The first workshop is virtual, Feb. 23, 24 and 25 starting at 6 p.m. and costs $30 to attend. In-person workshops are scheduled for March 23 in Mt. Vernon, Missouri, and March 25 in Lexington, Kentucky. Cost is $65 to attend and includes lunch. All three are expected to be approved for veterinarian and vet tech continuing education credits via RACE, as well as Certified Crop Advisor and American Registry of Professional Animal Scientists. Visit forages.ca.uky.edu/events for more information and a link to register.

Krista Lea, MS, coordinator of the UK Horse Pasture Evaluation Program, and Jimmy Henning, PhD, extension professor, both in the UK Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, provided this information.