Preparing for Catastrophic Flooding as Horse Owners

Seventeen inches of rain in 24 hours were recorded in McEwen, a small town in West-Central Tennessee over the weekend of Aug. 21. And no, 17 is not a typo.

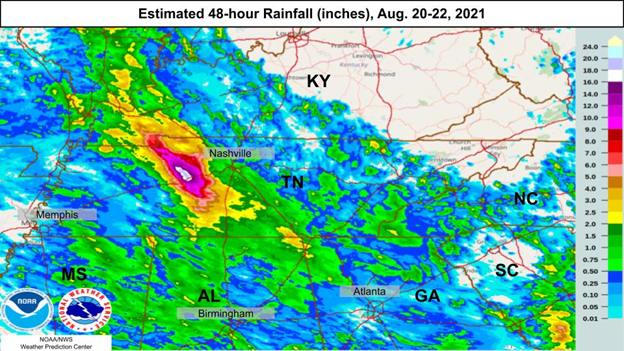

While not yet official, this would break the all-time 24-hour rainfall record in Tennessee by more than three inches. McEwen was one of many locations across this area that saw 8+ inches of rain (map below).

As you can imagine, this resulted in catastrophic flooding across this region causing 21 deaths with many others still missing. Property damage has also been immense, with homes lost and vehicles totaled. As the Tennessee Crop Progress and Condition Report summarizes, flooding left row crops and hay fields under water, tore down fences and damaged other infrastructure.

Like Tennessee, Kentucky has experienced its own share of catastrophic flooding this year and in the past. A few weeks ago, Governor Beshear issued a state of emergency following severe flooding across Nicholas County. While not as bad as the flooding in Tennessee, impacts included one death and severe property damage after some locations recorded 3-4+ inches of rainfall.

Kentucky also experienced historic flooding at the end of February when excessive rain fell across a stalled frontal boundary, leading to accumulations of 4-6+ inches across portions of South Central and Eastern Kentucky. Soils were already saturated from melting snow/ice and vegetation was dormant, leading to excessive runoff into streams and rivers. Some rivers broke all-time record crests. Below is one image showing the town of Beattyville under water.

All of these examples demonstrate one thing: We need to be prepared.

I always remind students in my meteorology class that they have probably seen multiple tornado warnings in their lifetimes but have never seen an actual tornado. You still need to take shelter. You can’t predict when the warning might turn into a tornado passing over your house. The same goes for flooding. You never know when a disaster like the flooding events in McEwen, Tennessee; Nicholas County, Kentucky; or Eastern Kentucky could occur in your neighborhood.

The best thing to do is prepare. I’ve talked about flood safety in previous columns, but being prepared for inclement weather, especially on a farm, is critical. There isn’t much we can do about row crops, but safe passage through severe weather for families, animals and buildings takes planning. Think about all the scenarios that could happen and prepare for each, making a plan for both family and farm.

I’ve put together a list of recommendations and questions to consider when thinking about emergency preparedness in relation to flooding, but many apply to other disasters.

Examine the landscape and determine safe areas during a flood event (higher elevations) and potential evacuation strategies. Be sure to prevent livestock from accessing flood-prone areas. Take into account the possibility of washed-out roads. Do you have a means for transporting animals? What if you have downed fence line, which happened in Tennessee? Will you have people (family, neighbors, employees,) you can count on to help?

Identify how you will receive warning information. This could include television, weather apps, radio or local outdoor warning systems. How will you get news if there is a loss of electricity? I recommend everyone have a NOAA Weather Radio. NOAA weather radios alert you to any warnings or watches across the area from your local National Weather Service office. They can be picked up for as little as $20-30 and can save your life. These devices also run on batteries. Of all the suggestions mentioned, I would make this one of the top priorities. Another thing you will need to consider is how will you send a warning in the case of communication failure. Do you have two-way radios available?

Make an emergency contact list. This may include neighbors, utility companies, local Cooperative Extension, veterinarians and emergency medical contacts. These contacts may be obvious to you, but what if you’re not there? Consider creating a wallet-sized card (the size of a business card) with the farm’s emergency contact information and distribute it to everyone on the farm.

Keep an up-to-date list of on-farm inventory. This can include farm machinery, livestock, acreage, electrical shutoff points and hazardous materials. Be sure that all animals can be clearly identified as your own.

You may already have a disaster supply kit for you home, but what about the farm? It’s always good to have some extra supplies on-hand for the unknown. I suggest planning for a week at a minimum, longer for drought scenarios. Your disaster kit might include alternative power supplies, extra fuel, dry bedding, additional feed for livestock, fence supplies and alternative sources of clean water. Also, fire extinguishers are a must for every building.

Review your emergency plan periodically. Things change and it’s best to account for all those changes before the next disaster. Replenish supplies, update contact information and learn from the past.

In the end, my advice is plan and prepare so you stay safe. While we’ve had our fair share of localized flooding disasters over the past several years, we can’t rule out even worse flooding in the years to come. Tennessee’s disastrous flooding is an eye-opener.

To drive home the danger of flooding, I want to take you back to 1937, arguably the worst flood in recorded history for the state of Kentucky. The National Weather Service in Louisville has a great writeup on the event, with eye-popping statistics. Overall, Louisville saw 15 inches of rain in 12 days (which shows how severe the Tennessee flood was) during the middle of January. Seventy percent of the city was underwater, and the flooding caused an estimated $3.3 billion in damage in today’s dollars. The flood crested 30 feet higher than flood stage. Below, I’ve included a picture that has stuck with me through my meteorological career. This poor horse got swept up in flood waters and eventually became entangled in a tree, where it died. Using the men as reference, it would roughly be 18 feet to the hind legs of the horse and 24 feet to the head. Fortunately, we do have much better infrastructure and flood control than what they did in 1937, but this picture tells an important story about the danger of flooding.

Matt Dixon is the senior meteorologist in the UK Agricultural Weather Center, which is part of the Department of Biosystems and Agricultural Engineering.