Roots: Building Healthier Pastures From The Ground Up

Horse owners and horse farm managers often think of pastures starting at the soil and representing all the biomass seen above the soil. But truly healthy pastures also have a rich network of roots below the surface. Astute mangers consider these when making management decisions. The roots of pasture grasses and legumes serve many functions: retrieving nutrients, holding soil in place during wet weather, housing a host of beneficial microbes and storing carbohydrates and minerals to support regrowth and overwintering.

If you buy into the phrase, “no hoof, no horse,” consider that a similar phrase, “no roots, no pasture,” is also accurate.

Plant Physiology 101

We all should know the basic concept of photosynthesis. Plants capture sunlight and use that energy to make sugars from carbon dioxide in the air. These sugars are the source of energy for growth or to store for later use. This energy, in the form of sugars or starch (carbohydrates), is stored at the base of the plant and in the roots and used to regrow leaves when the plant is defoliated by grazing animals, mowing or hay harvesting. Repeated, frequent defoliation will deplete the carbohydrate stores and physically shrink the root system until it lacks the volume to absorb enough nutrients or water to survive. Better management that results in thick and robust roots allows plants to quickly recover after defoliation and to better survive droughts because they are able to reach deeper into the soil in search of water and other nutrients.

Think of the soil surface as a mirror, whatever is growing above it is also what is growing beneath it.

Building Good Roots From the Beginning

When new pastures are being established, it is often recommended to take a hay harvest before the pasture is introduced into the grazing rotation. There is no magic to this recommendation at all, simply that most managers will not cut hay when the grass is only a few inches tall. By waiting for a hay harvest, it gives the plants time to grow tall, and therefore establish deep roots. Keep in mind that once cool season grasses begin to put up a seedhead (elongate), they are no longer using energy to build leaves or roots, because all energy has been diverted to seed production. For this reason, a hay harvest on newly-established pastures should be at the boot to early head stage (just as the seedhead is emerging from the leaf sheath). This will result in lower yield, but higher quality hay, as well as encourage the plants to grow down (roots) and out (new tillers) and form a dense sod.

If you don’t want to harvest hay, simply keeping the pasture mowed high will accomplish the same thing. Cool season grass pastures should be allowed to grow to 8-10 inches of leafy growth before grazing. Strategic mowing of new pasture is needed to keep weeds from overshadowing new grasses and to prevent seedheads from forming. Adjust the mower to clip pastures above the new grasses, therefore only removing weeds and seedheads. If pastures are allowed to get too tall and rank (excessive weeds or seedheads) then mowing will cause a thatch layer that can lay on top of new grasses and shade them out. If this is the case, then you may need to use a tedder to spread out the clumps or heavy thatch or remove the excess material as hay.

Managing Grazing for Good Roots

For those of us with established pastures, we can still have a great effect on root growth by controlling defoliation. This means 1) not mow pastures too frequently or closely and 2) graze rotationally, allowing pastures time to rest and rejuvenate.

Pastures are not lawns or golf courses and shouldn’t be managed as such. Mowing should not be dictated by the calendar but instead by the pastures and the needs of the animals grazing on them.

Here are the best times/reasons to mow a pasture:

- When animals have just been rotated off – this is to even out the pasture, so typically mowing around 3-4 inches

- When seedheads are growing - mow high enough to clip the seedheads of grasses or weeds but leave green vegetative material, which will drive regrowth and keep the ground shaded, typically around 8 inches.

- Before seeding – this is to open up the canopy, allowing sunlight to reach the soil surface for new seedlings. In this case, mow as close as possible.

Horses are notorious spot grazers, coming back to the same location to graze again and again while ignoring other areas. This could be because it is near the barn, a buddy in a neighboring pasture, shade or water or just out of habit. Because of this, even low stocked pastures will have some areas that are overgrazed and needing rest. Horse farms are also frequently overstocked, so often pastures are significantly overgrazed. In both cases, giving pastures a rest is vital to maintaining healthy grass and roots. Rest periods are best dictated by forage needs and availability, but a simple two weeks on, two weeks off rotation is a great place to start and will likely still yield many benefits. Pastures will be more resilient if you can maintain a 3 to 4 inch residual height as much of the year as possible, especially during the hotter months.

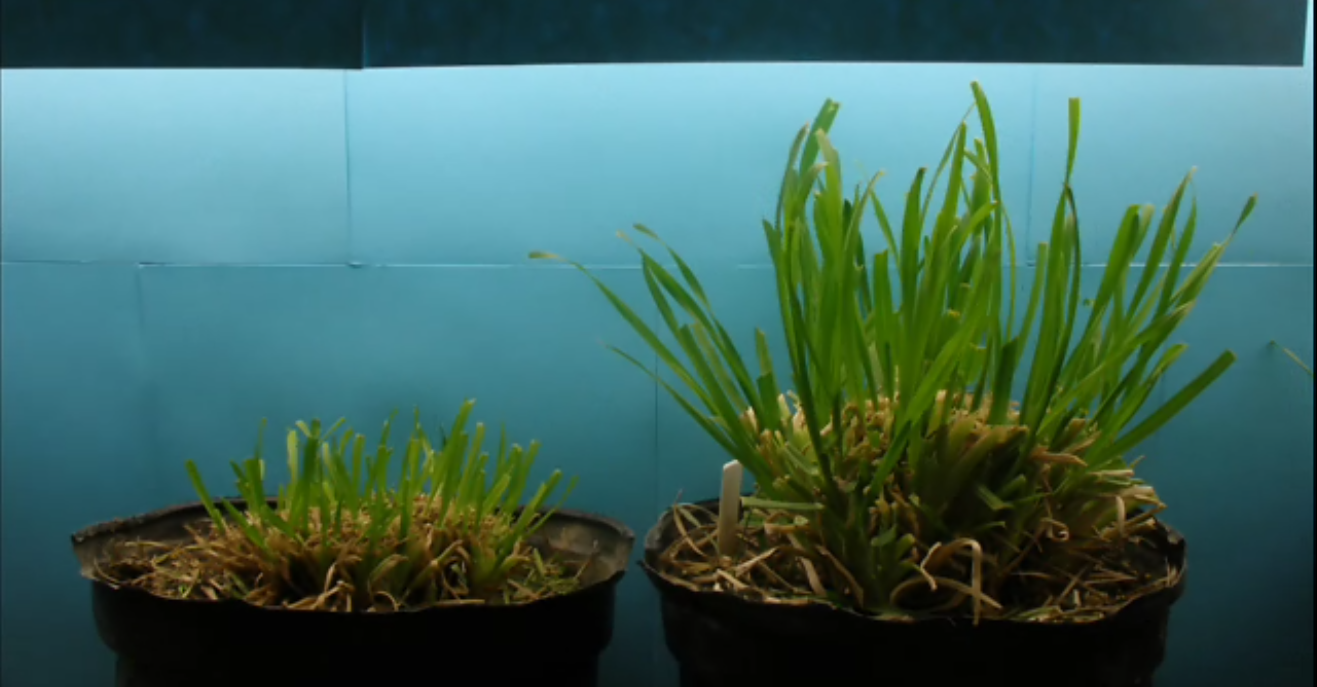

To demonstrate the effects of rotational vs. continuous grazing, the UK Forage Extension team put together a time lapse video of two orchardgrass plants. One plant was clipped monthly at 3.5 inches to simulate rotational grazing (right) while the other was clipped weekly to 1 inch for four weeks (left) to simulate continuous horse grazing. Five days of regrowth were then captured by video. The plant that was rested for a month with a 3.5-inch residual produced significant regrowth in just five days because it had sufficient root reserves that allowed it to rebound quickly. The continuously grazed plant produced little growth because root reserves were exhausted, and the low cutting height left few leaves to generate new energy. You can view the full video here.

One last thing to consider in root management is soil fertility. If soils are deficient in any required nutrient, the growth of the entire plant will be negatively impacted. Phosphorus is especially important to root growth and development but is rarely low in soils in Central Kentucky. A soil test can easily determine if phosphorus or other soil amendment is needed. For most pastures, fall nitrogen applications will also boost root growth as nitrogen stimulates grass growth and similarly speeds root growth.

Next time you walk through your pasture, take a moment to consider what you see above ground, and what that suggests exists below.

Krista Lea, MS, coordinator of the University of Kentucky’s Horse Pasture Evaluation Program, and Jimmy Henning, PhD, extension professor in the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, provided this information.