Stretching Dollars to Stretch Pastures

Horses are expensive. In fact, every part of them is expensive, from feed to shoes to barns to pastures. As an agronomist for the University of Kentucky, I’ve spent the last 11 years making recommendations on pasture improvements. But as a new farm owner, I’ve suddenly found myself facing the same struggles as many other farm managers and want to share how I have balanced what the experts say with what reality gives us. Today’s topic…fall nitrogen fertilizer.

The recommendation is easy: virtually all horse pastures need nitrogen fertilizer in the fall. Ideally, 30-40 lbs of nitrogen per acre in September and again six weeks later, or 50-60 lbs of nitrogen per acre once in October or early November. This year, I chose to apply just once in October for several reasons of varying legitimacy. 1) Some of our pastures have a fair bit of summer weedy grasses, such as nimblewill, which I don’t want to fertilize. October is past their active growth window and therefore will not encourage further growth and spread. 2) Fertilizer isn’t cheap, so one application is more budget friendly. 3) Convincing my husband to take the truck and get the buggy and fertilizer and hook to the tractor and spread the fertilizer and return the buggy takes a lot of effort. So, once it is.

However, when I went to local farm supply store to set all this up, I was faced with some new issues I hadn’t yet considered: Not only is the price of nitrogen fertilizer up drastically (urea was quoted to me at $720/ton and increasing daily), it’s also very hard to come by.

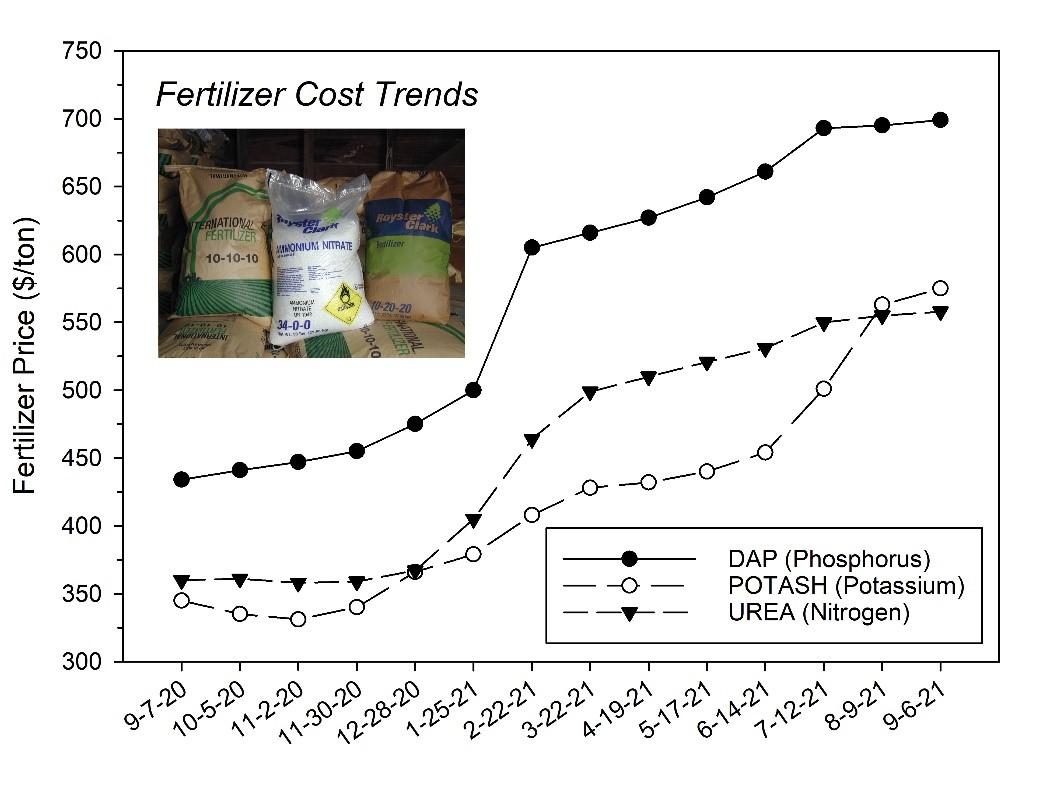

The graph in Table 1 illustrates the increasing price of urea as well as DAP and Potash for this fall. After speaking with several others, it sounds likely that these increases will continue into next year and are driven by weather delays, increases in natural gas costs and high shipping costs. The store I spoke with, that services many big Thoroughbred nurseries in Central Kentucky, also said they can’t swear they can get any more fertilizer this year, and if they do, it will likely be in November.

It would be easy to walk away from this right now, saying it’s too expensive and too scarce to be worth my time. But I know the benefits of fall nitrogen are worth the effort. Nitrogen is used in photosynthesis to create energy, which essentially means it helps the plant do whatever it’s already doing. In the spring, that is producing a seedhead. This is why hay fields are often fertilized in the spring, to boost yield. But pastures will have a natural flush of growth in the spring, and most horse farms, including my own, don’t have enough horses to utilize all that spring growth (nor should we). So we have to mow.

Fall is another story. At this time of year, plants are getting ready for winter. They are storing energy in their roots, producing new shoots, and expanding their leafy growth to protect their crown (the growing point close to the soil) from snow and cold. These are the things I want my grasses to do more of. Fall nitrogen helps plants stay green longer into the winter, survive the winter better and green up earlier in the spring. All of this translates to less hay feeding this winter without needing more mower time.

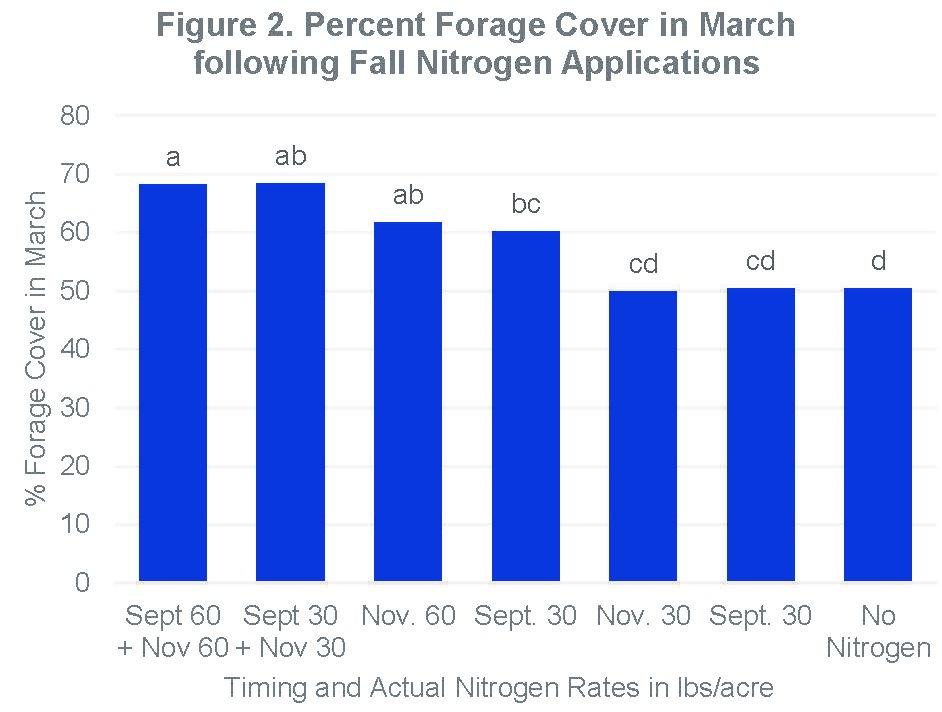

A study in 2006-2008 found that forage cover was nearly 20% higher on treatments receiving adequate fall nitrogen applications compared to the control or those with minimal nitrogen added. Figure 2 shows this data, and illustrates that 30 to 60 lbs of actual nitrogen twice in the fall, or 60 lbs in November, are statistically identical in their benefits for increased forage cover the following spring. A 20% increase in forage cover may not sound like much, but imagine if you didn’t have that cover, you’d likely have 20% more weeds in the spring. With this information, I believe, fall nitrogen is worth the effort.

So I have two problems facing me: price and scarcity. I can’t directly fix either of these, but I can adjust my plan to accommodate.

Clearly, fertilizing every pasture on the 28 acres I have is out of my budget at this time, so I had to think critically about where the fertilizer (assuming I get some) is best used. I have two larger areas that haven’t had horses grazing on them in several years, though I do hope to graze them soon. These areas have few weeds, excellent grass cover and likely good roots, so I can skip them to save some cash. Additionally, I have a few small paddocks that are (intentionally) overgrazed. In fact, desirable grasses are essentially grazed out. And I plan to winter a few horses on these, so there really isn’t any hope for survival of a stand here. I’ll skip them, and plan to overseed and rest these in the spring. Now I’m down to fertilizing about 10 acres, areas that have been grazed aggressively, but still have desirable grasses that could rebound with a boost. The price will still be high, but much more manageable.

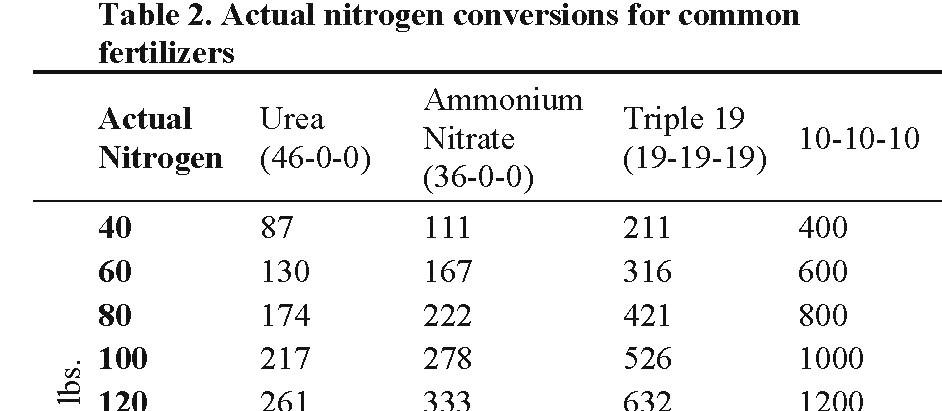

Now that I have a plan of where to fertilize, I need to find some. Before I start frantically calling every farm supply store I can find, I need to consider all the different types of nitrogen fertilizer. Nitrogen, in its pure state and under reasonable temperature and pressure, is a gas. In fact, the air we breathe is almost 80% nitrogen. But getting it into the ground in a usable form to plants is the tricky part. The most common form in Central Kentucky is urea, which is 46% nitrogen and 54% inert (CH4N2O for my fellow science nerds). Nitrogen can be applied in other forms, such as ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) as well as mixed fertilizers that contain sources of nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium. Table 2 contains actual nitrogen rates and how that translates in commercial formulations. Keep these in mind when you start comparing prices and shopping for alternatives. And if you find a price that too good to be true, it probably isn’t true.

My father-in-law was recently bragging on the cheap price he paid for triple 19 fertilizer and suggested I go that route. Triple 19 (labeled as 19-19-19) contains just 19% nitrogen, along with 19% phosphorus and 19% potassium. That means to apply my goal of 100 lbs of nitrogen per acre, I would need to apply 217 lbs of urea or 526 lbs of triple 19. So unless his Triple 19 is less than half the price, it really won’t save me any money. Additionally, this fertilizer would also add phosphorus and potassium to the pasture. Having completed a soil test back in the spring, I know my pastures are already high in both of these, so adding extra is simply a waste of funds and can potentially lead to runoff into nearby streams. Mixed fertilizers are beneficial when pastures need several amendments, but costly and environmentally unsound if used without a soil test.

In the time it took me to write this article, about 10 days, the price I will be paying for urea has increased more than $100/ ton. And with no end in sight, I gave the go ahead to lock in my fertilizer before it gets any higher in the hope that some arrives. Fall nitrogen isn’t essential to the survival of my pastures. I know that if I can’t find it, or can’t afford it, most of my grasses will still green up in the spring and once again provide my horses with plenty of grazing. I’ll simply need to start feeding hay a little sooner, and a little longer, and maybe need more weed control this spring if the stands are thin. But if I am able to find and pay for it, I know the efforts and expense will pay off next year with greener, healthier and more robust pastures.

Krista Lea, MS. University of Kentucky Research Analyst and UK Horse Pasture Evaluation Program Coordinator. Co-Owner and Manager of Texata Farms, LLC, a retirement and layup facility in Versailles, Kentucky.

References

Teutsch, C. and Grove, J. Navigating High Fertilizer Prices in Ruminant Livestock Operations. October, 2021, Cow Country News.

Schwer, L., S. R. Smith, C. Huo, T.C. Keene, J. Lowry, G. Roberts and J. Morrison. 2009 Late Fall Nitrogen Applications for Horse Pastures. American Forage and Grassland Council Annual Conference,.