Tall Fescue Risk Measured Through Field and Manure Measurements

Tall Fescue is a name that can evoke fear in many horse owners. Some of this fear is rightfully earned, some of it undue and some of it not sufficient. In Kentucky, late May through June is when we see tall fescue growing most rapidly, producing seed for next year and potentially causing the greatest negative impacts on our horses.

Tall Fescue is a name that can evoke fear in many horse owners. Some of this fear is rightfully earned, some of it undue and some of it not sufficient. In Kentucky, late May through June is when we see tall fescue growing most rapidly, producing seed for next year and potentially causing the greatest negative impacts on our horses.

It’s also the best time to look at pastures critically and evaluate the risk they pose to mares. Before we get to mitigation strategies, let’s review some tall fescue basics and look at some common myths about tall fescue and horses.

Tall fescue basics

- Tall Fescue (schedonorus arundinaceus (Schreb.) Dumort., nom. cons.) is a cool season, bunch-type grass native to Europe and naturalized in the Eastern U.S., particularly in the Transition Zone (area between the cold North and hot, humid South).

- It has good forage quality, yield and palatability, making it an excellent forage for horses.

- Tall fescue forms a symbiotic relationship with a fungal endophyte, which gives it added resilience to drought, pests and grazing. Without the endophyte, tall fescue would not persist like it does.

- The endophyte produces many ergot alkaloids, the primary one being ergovaline.

- Ergovaline (and other ergot alkaloids) can cause complications in late-term mares, such as prolonged gestation, thickened placental membranes, difficulty foaling (due to overgrown foals), increased foal and mare mortality and decreased milk production (agalactia).

- Early-term mares can experience prolonged luteal function, decreased breeding efficiency and early-term pregnancy losses, when consuming high levels of ergovaline.

- All other classes of horses, including stallions, growing horses and performance horses will experience vasoconstriction, but this appears to have much less impact and is therefore of less concern with these classes of horses.

Myth: We don’t have tall fescue

This belief is a common misconception. It is easy to think that if you haven’t had fescue issues in your mares before, you must not have tall fescue. This is rarely the case, though there are several reasons it might appear so.

The University of Kentucky Horse Pasture Evaluation Program began sampling pastures in 2005, looking at their botanical composition. In 15 years of sampling more than 250 farms, we’ve never found a farm that had no tall fescue and rarely found a pasture with less than 5%. On pastures with no recent renovation, we see tall fescue typically represents 15-20% of the total pasture. While this number isn’t high, it jumps significantly once you factor out the 30-40% of a pasture that is typically covered by weeds or no cover at all. Significant weeds or bare areas drastically increase the amount of tall fescue in the horse’s diet. Additionally, 70% or more of tall fescue plants in most Kentucky pastures are endophyte infected, which means it is very likely the tall fescue in your pasture is also infected with the endophyte.

So why don’t we see more cases of tall fescue toxicity? The answer lies in timing. The seasonal cycles of pastures and foaling mares don’t usually line up. Ergovaline, and other ergot alkaloids produced by the endophyte infecting tall fescue are not active in cold months. In central Kentucky, we usually see spikes of ergovaline from late April to early June. Because the majority of mares foal by the end of April, few are exposed to toxic levels of ergovaline.

But this fortuitous timing doesn’t always occur. Late foaling mares could be at higher risk simply because of their foaling date. And in mild winters, we sometimes don’t see ergovaline drop sufficiently. In this same time period, other cool season grasses are dormant and of low forage quality, meaning there is little to dilute the fescue. This is further compounded if the farm is feeding fescue hay or using fescue bedding. Cases of toxicity have been observed in January and February.

Myth: Horses don’t like tall fescue

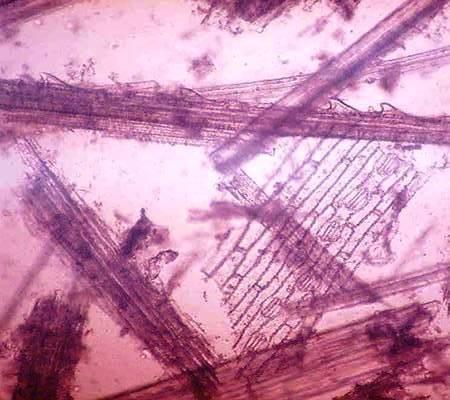

Given the coarse feel of tall fescue compared to the soft leaves of orchardgrass, it’s understandable why it has been assumed that horses would avoid tall fescue. But this is another dangerous assumption that is largely untrue. UK Plant and Soil Science PhD candidate Jesse Morrison used microhistological analysis of equine feces to determine diet composition on pastures. In this study, tiny grass fragments in manure were observed under a microscope and counted. Counts were compared to pasture composition measurements to determine if horses consumed certain species more or less than how frequently they appeared to in the field.

In both the spring and fall, eight half-acre paddocks were each grazed by a single horse for three days. Manure and species composition data were collected from each and the microhistological analyses were compared to pasture data. A strong correlation was found between the amount of a species found in pasture and the amount of plant fragments in manure for both tall fescue (r2=0.81) and orchardgrass (r2=0.57). This suggests that horses do not select for or against either species, but graze both species, as well as Kentucky bluegrass in a similar pattern as the availability of these grasses.

Horses are much more likely to decide where to graze based on other factors, such as buddies in a nearby pasture; proximity to the barn, water or shade; distribution of manure and urine; or simply where they’ve grazed before. It is likely that there is some variation in individual preference and tolerance to ergovaline as well.

Proven mitigation strategies

All hope isn’t lost just because you have some tall fescue. As we’ve seen before, every farm in Kentucky (and much of the Southeastern U.S.) has tall fescue. But there are several steps you can take to reduce the risk of toxicity on your foaling mares. Here are a few:

- Good pasture management. Fertilizing, seeding, weed management and rotational grazing can help you to reduce weeds and bare soil and increase desirable forages to dilute the amount of tall fescue in the total diet.

- Clip pastures. Ergovaline accumulates in the stem and the seedhead, so clipping to remove these reduces the overall concentration in the plant. Take care not to graze or mow below 3 inches, as ergovaline also accumulates at the bottom 3 inches of the plant.

- Avoid small paddocks. Managers often want to place their most valuable mare in a small turnout paddock near the barn to keep a close eye on her. Unfortunately, these paddocks are often heavily overgrazed and neglected when it comes to pasture management. Because of this, other grasses are grazed out and tall fescue is grazed close, resulting in high levels of ergovaline. On average, larger pastures tend to be better managed and therefore safer for mares compared to smaller paddocks.

- Test your local hay. While Western-grown hay has very little chance of containing much tall fescue, hay harvested from local grass fields certainly can. Fortunately, ergovaline is degraded during the drying process; therefore hay only contains about half the levels of pasture. But there can be potential for toxic levels in hay, especially when cut at the seedhead stage. Once the hay is baled and stored, ergovaline will stay in that hay for a year or more. A simple ergovaline test from UK’s Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory can rule this out.

- Consider a targeted herbicide to remove tall fescue. Herbicides with the active ingredient imazapic (Plateau is a popular brand) can effectively kill tall fescue in pastures while only temporarily stunting bluegrass and orchardgrass. This is a great option if you have a good stand of desirable grasses, are on steeply sloped ground or need to quickly remove tall fescue from pastures before foaling season. Read and follow all label recommendations for any herbicide and consider how you will fill in areas left bare.

- Start over. This sounds like a daunting task, but complete re-establishment has significant benefits. If a pasture is more than 50% undesirable, including toxic tall fescue, weeds, bare soil and annual grasses (crabgrass and foxtail), it is likely a good candidate for complete reestablishment. In one year’s time, a pasture can be turned from problematic to lush and productive. Be sure to start planning this step far in advance.

- Talk to your veterinarian about medical intervention. In some cases, daily doses of domperidone are the best option for alleviating the symptoms of toxic tall fescue and increasing the likelihood of delivering a live foal without complications and having enough milk to nurse.

- Remove mares from pastures. If time or other constraints prevent you from pasture interventions, keeping mares in the last 60 days of foaling in stalls or dry lots might be the best bet to prevent toxicity issues.

Conclusion

Tall fescue is found in pastures throughout Kentucky and much of the Southeastern U.S. and horses are unlikely to avoid it enough to prevent toxicity. To be the best managers of our broodmares, we must take additional steps of reducing or even eliminating toxic tall fescue in our broodmare pastures. Contact your local county extension agent for assistance in identifying and testing tall fescue and coming up with a mitigation strategy. Several good publications including how to sample tall fescue and how to establish new horse pastures can be found at forages.ca.uky.edu/equine. Special thanks to Jesse Morrison, PhD, assistant research professor in Mississippi State University’s Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, for the microhistological data.

A fact sheet about fescue can be found here: http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agcomm/pubs/id/id144/id144.pdf

Video resources can be found here: https://gluck.ca.uky.edu/ce

Krista Lea, MS, coordinator of the University of Kentucky's Horse Pasture Evaluation Program, and Ray Smith, PhD, extension professor in UK’s Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, provided this information